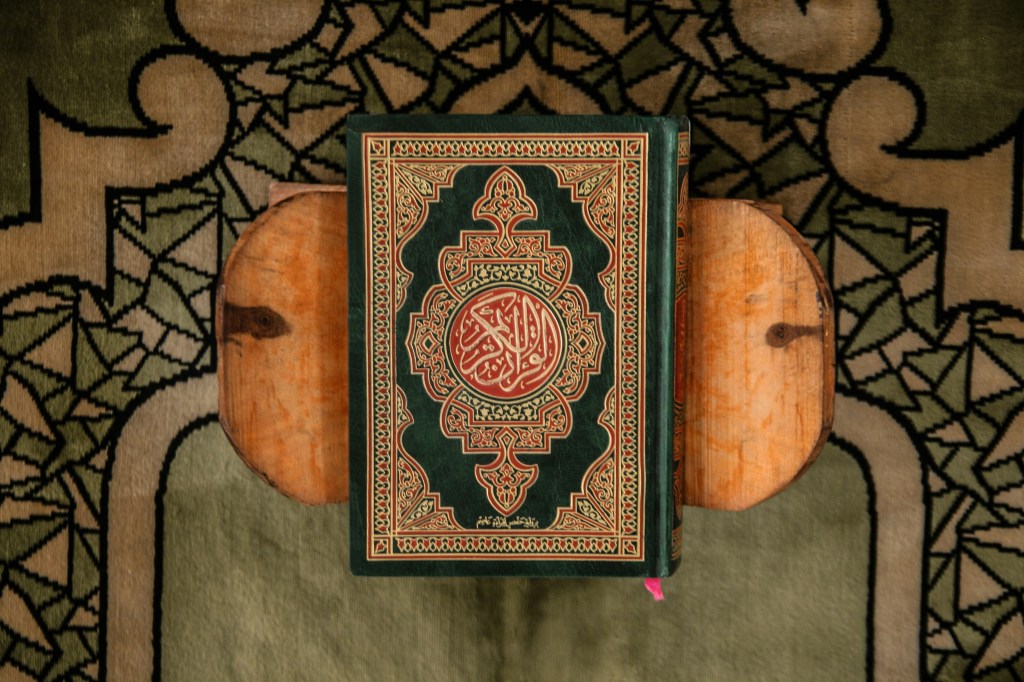

If you talk to Muslims about the Bible, or if you read the Qur’an, you’ll very quickly realize that Islam doesn’t teach that there are four gospels. No, the Qur’an, and the vast majority of Muslims, assume that Jesus came and revealed one book, called The Injil, i.e. The Gospel (Surah Al-Ma’ida 5:46). The Qur’an seemingly has no idea about the four separate books of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Why is this?

Some of this seems to be due to the Qur’anic worldview and its assumption that all true prophets bring their own heavenly book revelation with them for their specific people, such as the alleged ‘scrolls of Abraham’ (Surah Al-Ala 87:19). These prophets and their books are said to all contain the same basic message about turning from idolatry toward worship of the one creator God because the day of judgement is coming.

This is the narrative that Mohammad claimed about himself (Al-Ma’ida 5:48). Then, to try to defend his own prophethood when challenged, it’s also a narrative he forced onto the story every other prophet. Of course, everyone who has actually read the Bible knows that this is not true of every prophet, and not even true of many of the prophets the Qur’an is aware of, such as Abraham and Elijah. It’s not even true of Jesus. He didn’t come revealing a book from heaven; rather, he was the revealed Word of God, and his disciples later recorded his life and ministry in the four gospel accounts. This is yet another piece of evidence that Mohammed likely didn’t have access to a Bible he could read, though he does seem to have had access to lots of Jewish, Christian, and heretical oral tradition floating around in seventh-century Arabia.

However, this week I learned that there may be an additional reason why the Qur’an doesn’t seem to know that there are four gospels. This reason has to do with an early church figure named Tatian, who is a rather complex figure. Discipled by Justin Martyr, Tatian later returned to his home area of Adiabene, old Assyria, what is today N. Iraq, and proceeded to write a fiery treatise, “Address to the Greeks,” on why Christianity is superior to Greek beliefs – but also how he believed the East to be vastly superior to the West in general,

In every way the East excels and most of all in its religion, the Christian religion, which also comes from Asia and is far older and truer than all the philosophies and crude religious myths of the Greeks.

Significantly, Tatian seems to have been the first figure in church history to attempt to translate some of the New Testament into another language. Tatian combined the four gospels into one account, translating this work into old Syriac. This book was called the Diatessaron, and for several hundred years it was the primary form of the gospels used in the Syriac-speaking Christian world of the Middle East and Central Asia. A standard translation of the four canonical gospels didn’t take its proper place among the Syriac churches until a few centuries later. Tatian himself eventually drifted into some problematic asceticism and was proclaimed a heretic.

Here’s where Tatian connects with the Qur’an’s ignorance about the existence of four separate gospels. The Diatessaron was very popular in the broader Syriac-speaking region – a region that overlapped considerably with the territory of Arab kingdoms and tribes. Biblical scholar and linguist Richard Brown puts it this way in his paper, “ʿIsa and Yasūʿ: The Origins of the Arabic Names for Jesus,”

For several centuries, the Diatessaron was the standard “Gospel” used in most churches of the Middle East. When the Quran speaks of the book called the “Gospel” (Arabic Injil), it is almost certainly referring to the Diatessaron.

Why doesn’t the Qur’an seem to understand that there are four gospels? There is a good case to be made that this Islamic confusion about the actual makeup of the New Testament goes back to a well-intentioned project of an early church leader.

In this, there is a lesson to be learned about the unintended consequences of pragmatism in mission contexts. It’s not hard to see how those in the early church, like Tatian, might have felt that it would be more practical and helpful to have one harmonized gospel book instead of three very similar synoptic gospels and one very different Gospel of John. For one, it would have been much cheaper to copy and distribute. Books were very costly to produce in the ancient world, often requiring the backing of a wealthy patron. In addition, a single harmonized account would have also seemed simpler to understand, rather than asking the new believers in the ancient Parthian Empire to work through the apparent differences between the timelines and details presented in the four separate gospel accounts.

What could be lost if the Word of God were made more accessible in this fashion? Well, for one, this kind of harmonization loses the unique message and emphasis present in the intentional structure and editorial composition of each book. The authors of the Gospels were not merely out to communicate the events of Jesus’ ministry. They were also seeking to communicate the meaning of those events by how they structured their presentation of them. For example, consider how Mark sandwiches Jesus’ cleansing of the temple in chapter 11 between accounts of Jesus cursing the fig tree. This structure is intended to communicate to the reader that the cursing of the fig tree was a living (and dying) metaphor of the fruitless temple system of the 1st century – and its impending judgment.

Tatian’s pragmatic decision cut off Syriac-speaking believers from so much of this crucial meaning because he did not simply translate the four individual gospels. Further, he also inadvertently contributed to confusion among the ancient Arabs about the nature of the Injil, a confusion that was later codified in Islam and continues to trip up Muslims to this day, creating doubts in their mind about the validity of the four gospels.

If you find yourself in conversations with Muslim friends about this question of why there are four gospels instead of one, knowing this background might prove helpful. The Qur’an itself doesn’t know that there are four gospels. This is because of its own errant understanding of prophethood – an understanding, unfortunately, aided by some ancient and pragmatic missiology.

We need to raise 28k to be fully funded for our second year back on the field. If you have been helped or encouraged by the content on this blog, would you consider supporting this writing and our family while we serve in Central Asia? You can do so here through the blog or contact me to find out how to give through our organization.

Two international churches in our region are in need of pastors, one needs a lead pastor and one an associate pastor. If you have a good lead, shoot me a note here.

For my list of recommended books and travel gear, click here.

Photo from Unsplash.com