We just traveled back to the US for a medical leave. Once again, when crossing worlds from Central Asia to the States I was struck by a peculiar flipping of the condition of bodies and infrastructure. I wanted to write about it while the contrast is still fresh to my eyes, knowing that sometime in these first weeks I will lose that ability to notice the stark contrasts as my immediate surroundings register in my brain as the new normal.

For an interesting experiment, ask those who are newly visiting or moved to your area what jumps out at them, what their senses and mind can’t help noticing. It’s a reliable way to get fresh perspective on your immediate surroundings – surroundings your mind has already lost some ability to “see” as they have become the proverbial water the fish is surrounded by.

In short, when traveling from Central Asia to the West, the bodies get more broken, while the infrastructure gets less so.

The shift in infrastructure happens quickly. Most of the building supplies and goods available in our corner of Central Asia are a lower level of goods made in Asia for export to the developing world. You have goods made in China for the West. Then you have goods made in China for places like Central Asia. These are not the same. Disposable plates crumble into your kebab, headphones bought in the bazaar last a week and zap your ears with electric current, playground equipment cracks and warps. While Central Asian culture cares more for a certain sheen when it comes to its infrastructure – such as shiny door knobs and fancy ceiling panels – shortcuts in quality mean things fall apart remarkably quickly. One starts longing for solid everyday things – like toilet seats – that would actually last for decades. Yes, the quality of toilet seats does indeed have serious implications, and is one area where you very much want to get the Made-in-China-for-the-West variety.

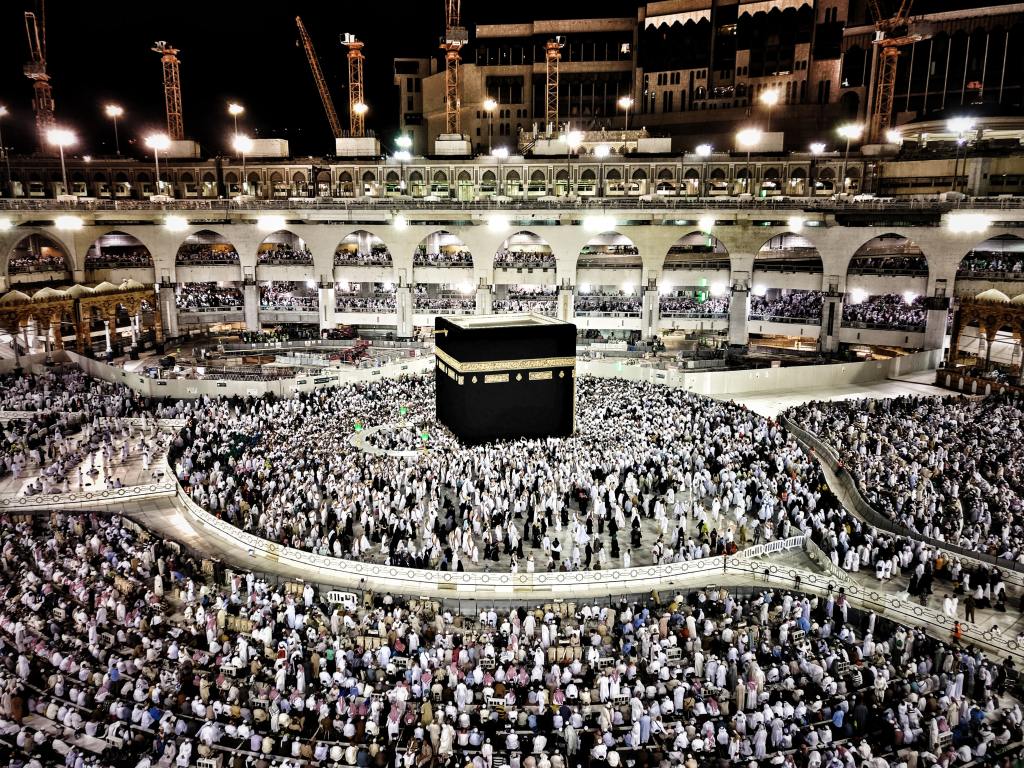

Essentially, the infrastructure gets firmer as you transit through the Middle East to the West, getting broader, thicker, and simply less easily broken, culminating upon arrival in the US where even the luggage carts look like they have been working out, compared to their frail foreign cousins. You may catch yourself admiring a metal fence and wondering about the foresight of those willing to spend so much money on something so solid. Buy once, cry once, as a wise American deacon once said to me.

The human bodies seem to move in the opposite direction. In general, the population of Central Asia is on the younger side. The “baby boom” peak of our local area are those born in 1990. The diet is also significantly healthier. Fresh fruits and veggies are cheap and a central part of the local diet. As are fresh yogurt and pickled veggies, full of good probiotics. This seems to balance out all the bread, oily rice, and sugary chai locals consume on a daily basis. While some of the younger generation is being raised on fast food and beginning to develop obesity, most of the population would be in healthier weight ranges. Fathers and Grandpas typically have a bit of a stomach, good for resting their chai saucer on. Mothers and grandmas end up naturally a little heavier as they age, bearing children and caring tirelessly for the household. In short, bodies develop and age in a way that has been typical for much of human history.

However, moving Westward means moving into a world where the bodies are significantly more broken. Weight and diet are a big part of this (why are fresh veggies so crazy expensive in Western societies?), but are not the only one. It seems like a strange disrespect for the body accompanies the West’s public infatuation with model-standard physicality. When you’ve lived outside North America and reenter, it’s not unusual to be hit with a sense that something is deeply wrong with our body culture when getting on that first plane with other Americans, or when being hollered at by that first wave of TSA agents. It’s as if in the West we either worship our bodies and fight to preserve their youth for as long as we can, or we come to neglect and hate them. I myself have struggled with a spiritual form of this neglect, believing for many years that I could ignore the body if I was sacrificing it for ministry. My struggle is easier to hide than many of my fellow Westerners, since I atrophy when I neglect my health, rather than putting on weight. But we share in the same root malady. Something about the Western experience has caused us to believe we are no longer actually embodied.

Along with this, the West is also aging. The average traveler in American airports is at least middle-aged, if not older. There are very few children in Western airports. And those that you see are usually those of immigrant families from other parts of the globe. Even flight attendants and airport staff have a different posture toward children, with those of Central Asian or Middle Eastern culture being far more likely to happily accommodate the needs of those with little ones, whereas Western staff are not unlikely to find such families an inconvenience. It goes without saying that older bodies are more broken bodies, although this is a more natural brokenness, as opposed to that caused by the Western lifestyle.

The bodies get more broken, while the infrastructure gets less so. I notice these things not really knowing what they fully mean. But for a student of culture, the path toward understanding significance starts with observation, and then a long-term chewing on those observations until clarity suddenly drops. At the very least, noticing these weaknesses of culture keep us from an unhealthy pride in either one. Every watered valley has its jackal, as one of our local proverbs wisely says. Post-fall, our brokenness will manifest not only on the individual level, but also on a scale culture-wide. This should sober us and keep us from both culture despising and culture worship.

There may be cultures that have the moral capacity in this age to care for the physical body as well as well as the quality of the things we build around us to serve the body. Unfortunately, these things seem to currently be a trade-off of sorts. For now, it’s for the Church to seek to model this kind of stewardship, strangers and exiles though we are. For though the temporary physical things of this world will pass away, we are still to plant gardens in our Babylon. We do this freely, knowing that we have a city, and bodies, that are coming and that will last forever. Long after the finest body – or luggage cart – has turned to dust.

Photo by Grimur Grimsson on Unsplash