We crawled out of a hole, but fell into a well.

Regional Oral Tradition

Missions, Wisdom, History, Resurrection

We crawled out of a hole, but fell into a well.

Regional Oral Tradition

Many cultures’ folk religions believe in the evil eye. In our area of Central Asia, some, particularly the elderly and rural, believe that certain persons secretly have the power to curse others by looking at them and envying them. This is said to be the evil eye, or the dirty eye as our local language puts it. In order to protect one’s self from this danger, certain eye amulets can be hung on persons, gifts, or in rooms.

It’s also important to assure others that you are not a secret possessor of the evil eye. Locals do this by prefacing a complement with the Arabic phrase, Mashallah, which means “what God has willed.” In complementing babies and small children, one should say, “Mashallah, what a cute baby!” This supposedly protects the child from an intentional or unintentional curse from the evil eye. Mashallah is also plastered on houses and vehicles in order to protect them from this curse.

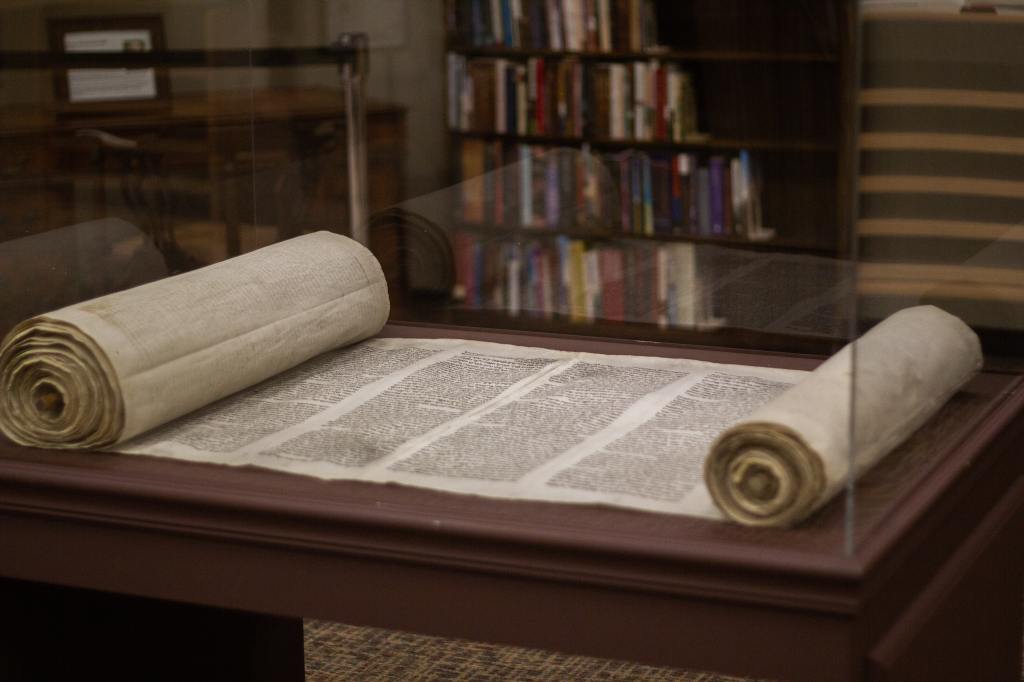

I knew that the evil eye is a widespread belief in the Middle East and Central Asia. I had even come across it in strange places in Western history. Those unique geometric designs painted at the apex of Amish barns? Artistic descendants of attempts to protect their barns from the evil eye. But I had no idea just how ancient this belief in the evil eye is. Look at this Akkadian language (think roughly 2500 – 500 BC) evil eye incantation from the archives of ancient Assur.

The [eye] is evil, the eye is an eye which is evil, the eye is hostile… the eye which emerges is the eye of the terror of the enemy; (namely), the eyes of father, the eyes of mother, the eyes of brother, the eyes of sister, the eyes of a neighbor, the eyes of a (female) neighbor, the eyes of one who cares for or carries (a child).

The eye called out maliciously (at the) gate, the thresholds groaned and roofs shook. In the house which it enters, does the eye wreck (things)!

It has wrecked the potter’s furnace and caused the sailor’s boat to sink, it has smashed the yoke of the mighty ox, it has smashed the shin of the loping donkey, it has smashed the loom of the skillful weaving-ladies. It has removed the loping horse and the nose-rope of the plow-ox, it has scattered the bellows of the furnace when lit. It has deposited worm-pests at the command of the murderous Adad, it has raised quarrels between (otherwise) happy brothers.

Smash the eye, chase away the eye! Make the eye pass through seven rivers and make it pass through seven canals! Make the eye pass over seven mountains! As for the eye, take it and bind each of the joints of its feet. As for the eye, take it and smash it like the oil-pot of a potter in front of its owner. Whether fish in the river or birds of heaven, (the eye) causes them to fall/sink and destroys them. Whether one’s father or mother or brother or sister, or stranger or…

Akkadian Incantation, ESV Archaeology Study Bible, p. 1270

Westerners struggle to feel the fear the evil eye has exerted over huge swathes of humanity. We tend to write it off as mere superstition. Even as Christians who believe in the power of the demonic, we are likely to miss when this belief might need a direct Christian response among our focus people groups. Yet for many, they are just as emotionally terrified of the evil eye as they are of Covid-19. It is real to them, even if it does not feel real to us.

What might a Christian response look like? Certainly the theological knowledge that the indwelling power of the Holy Spirit now protects believers from whatever demonic power could be manifest in the practice/belief of evil eye. He that is in you is greater than he that is in the world (1st John 4:4). Practically, all evil eye amulets should be discarded and the use of Mashallah discontinued as evidence of believers’ trust in Jesus for protection in the spiritual realm. It may also be appropriate to craft Christian prayers where believers actively “put on” the righteousness of Christ and the truth of God’s word, reaffirming their faith in God against their fears that the evil eye could still harm them. For one historical example of this kind of prayer, check out St Patrick’s Breastplate.

Whatever our response ends up looking like, it’s worth keeping “an eye out” for belief in the evil eye. This belief is surprisingly ancient and still surprisingly widespread.

Photos by Hulki Okan Tabak and Ella Christenson on Unsplash

Most Western cultures tend to be time-oriented. This means they respect others by respecting their time, by prioritizing the clock. Most Eastern cultures tend to be event-oriented. This means they respect others by respecting their participation, by prioritizing their access the key parts of an event.

Both cultures value respecting others. It’s the how in respecting others that often results in a culture clash.

Think of a typical church small group in a university city. This group meets once a week for fellowship, bible study, and prayer. Let’s say our hypothetical group’s participants are made up of both Westerners and those from the global East, perhaps Indian grad students and business professionals.

All of the members of this small group have agreed to a start and end time for their meetings, 7:00-9:00 p.m., and they have consensus as to the parts of the gathering: fellowship, study, and prayer.

The evening for the group’s meeting arrives and some of the participants are on time. However, after 5-10 minutes, the Westerners feel the urge to begin the meeting. This doesn’t sit well with the Easterners, because several members of the group have not arrived yet. They feel like it would be very unloving to start the meeting without all the participants present. The Westerners for their part want to start because they feel it would be very unloving to not end on time. There are other things scheduled after the meeting, including the bed times of small children!

The meeting gets started eventually and the discussion goes longer than expected. Because it’s almost 9:00, the Westerners suggest that they skip the prayer portion of the event. After all, they want to honor everyone’s time by finishing on time and keeping their word. But the Easterners once again protest. It’s more honoring to make sure the group gets to pray together and fulfill all the key elements of this event, no matter how late it goes!

This is a classic collision of time-orientation vs. event-orientation, West vs. East.

You can see how different understandings of respect could lead to some uncomfortable disagreements in a group like this. But things could get even worse if any members of the group begin to elevate these cultural preferences to become matters of godliness. A Western brother might say that it’s more godly to manage time responsibility – redeem the time and keep your word, that’s what Christians should do, regardless of culture. An Eastern brother might differ that it’s more godly to prioritize people over schedules – love for others is how the world will know we are Jesus’ people, not by our rigidly managed schedules. And why do you let the clock cause you to neglect the great duty of prayer?

How do you get past this kind of impasse? On a practical level, it’s helpful if there are participants who can point out the cultural dynamics that are going on. Being aware of these differing cultural values of time-orientation and event-orientation help keep the conflict at an appropriate level – one of preference and not one of faithfulness. Pulling back the veil on the cultural elements at play helps to defuse the conversation, as many from each respective culture simply may have never heard before that there are others who approach respecting others in these different ways. It’s helpful to frame it as more like a personality difference and less like an issue of disobedience. This can inject some grace and readiness to listen into the conversation.

It’s also key to focus on the common and biblical virtue, respecting and loving others, that both groups are pursuing. They are working for the same biblical principle, but are applying it differently. This means the conflict falls in the realm of Romans 14-type issues. “The one who eats, eats in honor of the Lord, since he gives thanks to God, while the one who abstains, abstains in honor of the Lord and gives thanks to God” (Rom 14:6 ESV). In Romans 14, the same biblical principle of honoring the Lord and giving him thanks can be applied either by eating or by abstaining from eating. There’s a spectrum of faithful applications of this principle. This is also true of the other issue Paul raises in this chapter, honoring certain days over others.

Some biblical principles are given along with a narrower prescribed range of biblical applications, such as the Lord’s Supper. But many, many biblical principles are given to us with a broader range of possible applications. When we assume our own personal or cultural applications are the same as the biblical principle (sometimes we even do this in the name of fighting relativity), we tend to trample on Christian liberty and fight about the wrong things. We can divide the body of Christ over silly things like food, just like Paul warns about. Instead, we can join Paul in asking, “Will you, for the sake of honoring the clock, destroy the one for whom Christ died?”

If the conflict has made it this far, recognizing the cultural clash going on and identifying how the biblical principle and possible applications relate, they still have some work to do. How should the group actually proceed given these seemingly-exclusive preferences? Context plays an important part in making a game plan at this point.

Is one group the overwhelming majority of the attendees? Then it’s likely that the small minority should, for the sake of love, shift their cultural preferences to that of the majority. Is one group more able to shift culturally, more able to see both sides of the issue? Perhaps the younger members of the group would be more able to forgo their cultural preferences whereas the older members would risk violating their consciences. If so, the younger may be called on to make that shift for the sake of the others. Perhaps there is a way that both groups can prefer one another and meet in the middle with an intentional compromise. Or, perhaps different gatherings can prioritize the culture of the respective groups. This could even become fun: “First and third week of the month, we’re meeting Western style, second and third, it’s Eastern all the way! Prepare accordingly.”

Whatever practical solution our hypothetical small group decides upon, it’s likely that they will have grown simply by getting greater clarity on these differences and by working for an intentional solution. Too often cultural conflicts occur without the participants understanding what’s actually going on. Often, the majority just continues to do things its way and the minority feels like they weren’t heard or understood. Or, these conflicts get mislabeled as black and white issues of faithfulness when they were really just grey issues of preference.

These kinds of conflicts actually represent an important opportunity for growth and love – one which can witness powerfully to an unbelieving world with its merely skin-deep diversity. If you are a Westerner, you can learn to honor your Eastern friends by prioritizing everyone’s participation and by letting go of hard start and end times as possible. Show your Eastern friends that they are more important to you than the clock is. If you’re an Easterner, you can learn to honor your Western friends by showing them you value their time and their plans. Show them that you love them by helping them keep their commitments. How can you learn how to actually do this with real people? By asking questions about these preferences and by being a good listener. Simple spiritual friendship goes an awfully long way toward overcoming cultural differences.

These are, of course, broad strokes and exceptions always exist to these patterns. Yet in an increasingly globalized world, the church would be helped to be more aware of this very common culture clash. Let us work for diverse biblical cultures within our churches where we are time-oriented and/or event-oriented with gospel intentionality.

*If you want to learn more about time-orientation vs. event-orientation, Sarah Lanier’s book, Foreign to Familiar, is a great place to start.

Photo by Mitchell Hollander on Unsplash

There’s a fascinating book called Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes, by Kenneth Bailey. The premise of the book is that the life and ministry of Jesus can be better understood when viewed through the lens of Middle Eastern culture, of which Jesus was a native. It’s a good read and I highly recommend it.

Having lived myself in the Middle East and Central Asia, I’ve found other parts of scripture are also unveiled as I’m able to see them informed by these cultures. Consider this interesting back-and-forth between Abraham and Ephron the Hittite in Genesis 23:

[7] Abraham rose and bowed to the Hittites, the people of the land. [8] And he said to them, “If you are willing that I should bury my dead out of my sight, hear me and entreat for me Ephron the son of Zohar, [9] that he may give me the cave of Machpelah, which he owns; it is at the end of his field. For the full price let him give it to me in your presence as property for a burying place.”

[10] Now Ephron was sitting among the Hittites, and Ephron the Hittite answered Abraham in the hearing of the Hittites, of all who went in at the gate of his city, [11] “No, my lord, hear me: I give you the field, and I give you the cave that is in it. In the sight of the sons of my people I give it to you. Bury your dead.” [12] Then Abraham bowed down before the people of the land. [13] And he said to Ephron in the hearing of the people of the land, “But if you will, hear me: I give the price of the field. Accept it from me, that I may bury my dead there.” [14] Ephron answered Abraham, [15] “My lord, listen to me: a piece of land worth four hundred shekels of silver, what is that between you and me? Bury your dead.” [16] Abraham listened to Ephron, and Abraham weighed out for Ephron the silver that he had named in the hearing of the Hittites, four hundred shekels of silver, according to the weights current among the merchants. (Genesis 23:7–16 ESV)

Sarah has just died and Abraham seeks a place to bury her in the land where he and his household are nomadic sojourners. So Abraham and Ephron enter into a curious exchange over what to pay for the field and cave that Abraham desires.

In ancient Near Eastern culture, and to this day in that part of the world, generosity and honor are some of the highest virtues. Men seek above all to avoid the appearance of greed or stinginess. Rather, they seek to be hospitable, magnanimous, and honorable.

In this very public and potentially tense exchange between Abraham, the wealthy immigrant, and Ephron, the native (perhaps living in the twilight years of the Hittite empire), it is important that both sides uphold their own honor and the honor of the other party. Both sides need to save face, but they also need to get business done. Sarah has died and it is important to bury her quickly. Abraham needs to find out the price of the field and get permission to buy it. Ephron needs to demonstrate that he is acting honorably toward this sojourner and that he is not greedy for money. Here is how the dance commences:

Notice how both men were able to get important business done while maintaining one another’s reputation and honor in the eyes of the community. Ephron is able to say that he offered the field for free and Abraham is able to say that he paid was justly Ephron’s due. For both to save face, Ephron’s refusal to accept money for the land had to be understood as what it was, an offer made as part of a very public honoring of Abraham, but not one that he actually wanted Abraham to take him up on. On the other hand, if Abraham had simply taken Ephron up on his offer of free land, the community would likely have been shocked and Abraham’s reputation would have taken a hit.

Why the dance? Why not just speak more directly for the sake of efficiency? Welcome to the complexities of living in a society that values honor and respect more than efficiency and directness.

I had a very similar exchange like this happen today, when texting a colleague’s language tutor. I asked him how many lessons’ payments we owed him. The dance went like this:

Tutor: “About the lessons, let it be Mr. AW, I don’t want to get money for those lessons.”

Me: “Mr. Mhmed, it’s no problem at all. Another teacher has already offered to bring it to you. Just let me know how many lessons you had and I will tell him.”

Tutor: “Mr. AW, just three hours and fifteen minutes, but for me it’s no problem if you let it be.”

Me: “Thank you so much Mr. Mhmed. We appreciate your kind help in teaching our colleague.”

I then went on to set up the delivery of payment for the language lessons. Even though Mhmed said he didn’t want me to pay him for those hours, I have learned that it is important to pay it anyway and to graciously push past my friend’s honorable offer.

A Westerner might initially feel that these offers are disingenuous or even dishonest. Were Ephron or Mhmed being dishonest by making offers they weren’t wanting others to actually accept? I don’t think that’s what’s going on. Offers like this need to be understood more in the realm of poetic flourish, an important way of verbally communicating respect. They are real gestures of respect and generosity, but it’s very important that neither side take them as literal offers. For a rough parallel, think about our own saying: I would give you the shirt off my back.

A former colleague once accepted a delivery driver’s offer of a free pizza. This Midwesterner was new in Central Asia and was thrilled that this kind delivery driver wasn’t going to make him pay for his pizza. “Wow! They’re so nice in this country!” The driver walked back to his motorbike, paused, then sullenly returned to my colleague’s door.

“I’m so sorry, if I don’t bring back the money for this pizza, I will lose my job.”

My colleague was of course mortified that he had almost cost this man his job by taking his offer too literally. We missionaries have all had to learn over time that it’s important to push back at least three times when a shop owner, taxi driver, or anyone offers us something for free. By not accepting these generous offers, we enable the one making them to save face as a generous person, and we also save face as those who don’t take advantage of others.

Like Ephron, many from Middle Eastern cultures simply consider it polite to offer something two or three times, even if they can’t actually afford it. They in turn expect others to decline these offers several times, and then if appropriate (such as an offer for tea) to accept it graciously at the third or fourth offer or in some indirect fashion such as, “please don’t trouble yourself.” While Western mamas teach their kids to say please and thank you, Middle Eastern mamas teach theirs to say no the first few times, even if they desire to say yes.

It’s all a part of the honorable dance, still going strong thousands of years after Abraham and Ephron took the floor.

Photo by Bruno van der Kraan on Unsplash

The three adjectives – “genrous, handsome, brave” – used to describe the murdered man are a summation of the Iron Age moral code, a code that shines out clearly in all early literature (whether Gilgamesh, the Iliad, or the Tain) and that mysteriously survived in Ireland long after its oblivion in more sophisticated civilizations – and that endures to some extent even to this day… But there is also an unnamed virtue, hidden in these trinities: loyalty or faithfulness… In the heroic eras of various societies, including Ireland’s, loyalty served as the foundation virtue.

Cahill, How the Irish Saved Civilization, pp. 94-95

Loyalty above all. Generosity, beauty, and bravery as worthy of poetry and song. Sounds an awful lot like the traditional values of my Central Asian friends, though clothed now in an Islamic veneer. It seems to have hung on at the fringes of empires, protected by hard-to-reach places like islands, mountains, and deserts.

Photo by Ricardo Cruz on Unsplash

There are some passages of scripture that we tend to merely skim before quickly moving on. For me, the genealogies were definitely that kind of content. Sure, I believed that all scripture is God-breathed and useful for teaching and instructing in righteousness (2 Tim 3:16). But it was awfully hard for me to see how the genealogies would actually impact my life as a believer or be relevant in evangelism. “Perez the father of Hezron, and Hezron the father of Ram” is not exactly the inspirational material that typically shows up on Christian embroideries. Sure, the genealogies served an important historical purpose, but I assumed that was about it. I would be proved powerfully wrong.

When my friend *Hama agreed to read the Bible with me, we started in the book of Matthew, probably for the simple reason that it was the first book in the New Testament which I had given him in his language (The Old Testament wouldn’t be published for another 8 years). As a twenty-year-old new to the Middle East, this would be my first time studying the Bible with a Muslim friend. So why not start with Matthew?

I was not expecting the first half of the first chapter to deal such a blow to my friend’s worldview.

“Bro,” Hama said. “Jesus is incredible.”

“I agree. But why do you say that?” I replied.

“Look at his family line… look at all of the prophets in his line. There are so many, starting all the way back at Abraham. Bro, I never knew this.”

“And?” I was not understanding why we shouldn’t just take note of this neat historical content and move on the meatier portions.

Hama’s eyes had that far-off look he got whenever his mind was working hard. He seemed conflicted.

“…Mohammad doesn’t have a family line like this… he doesn’t have any kind of lineage to compare to this.” Hama was disturbed.

I didn’t know this at the time, but genealogy, specifically the father-line (patrilineage) is a cornerstone of Middle Eastern and Central Asian identity. You are who your fathers were. Their honor and their shame is imputed to you and your success and the success of your descendants depends on being able to draw upon an honorable reputation rooted in ancestry. A traditional Middle Easterner must be able to name their male ancestors at least to the seventh generation. Even though this is becoming a little less common among the modern and urbanized, it still is a primary lens through which people understand who they are and who others are. Your father-line makes a claim about you; it is a message in itself.

Hama was seeing something in Matthew in his first reading that I had never seen despite many years of devotions in Matthew, sermons, and bible classes. His Middle Eastern culture was helping him to understand implications of the text that I had missed as an American raised in Melanesia. In this and many other areas, Hama’s culture was not too far off from Jewish New Testament culture. He saw Matthew 1:1-17 as a devastating blow against what he had been taught his whole life – that Mohammad’s lineage was just as strong as that of the other prophets.

Yes, Islam maintains that Mohammad was descended from Abraham via Ishmael, but from Ishmael to Mohammad spans over two thousand years of plain old human without a whiff of inspired revelation. But Jesus, his line contained Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Judah, David, and Solomon! And all of them descendants of Abraham through Isaac’s line, not Ishmael’s. Jesus’ claims therefore to be The Prophet of Prophets are bolstered by this amazing pedigree. Mohammad’s seeming emergence out of nowhere six hundred years later as “the seal of the prophets,” in this light, appears to be unnatural and not in keeping with how God acted in history – always sending his prophets through Isaac’s line and with a strong prophetic father-line.

It was a blow that shook Hama’s world. It’s easy to take for granted religious claims that everyone around you simply repeats your whole life. But when faced for the first time with a compelling counter-claim, that’s when we get a true sense of just how strong a case our belief actually has. Sure, everyone in the bazaar says that Mohammad’s descent from the prophets legitimized his claims. But Matthew, in a thoroughly Middle Eastern way, had just thrown down the gauntlet.

It wasn’t the only way in which God would vindicate the gospel’s truth to my friend Hama, the jaded wedding musician. But it was a powerful start. One that I at least had never anticipated. Yet this is exactly what happens when we work through scripture with those who are different from us. We see new aspects of the text’s meaning, not different meaning, but insights uniquely apparent to those from other cultures. The diamond gets turned to reveal new beauty that was there all along. The Holy Spirit uses passages we gloss over as the vehicle for his convicting work. This argues, by the way, for the importance of working through books of the Bible systematically in our cross-cultural evangelism and discipleship – we just don’t know where exactly in the text the lightning is going to strike. And it may be where you never expected it.

Photo by Taylor Wilcox on Unsplash

We reformed-types can sometimes be quite skeptical about the value of studying culture(s). “Why should I study culture? I know Romans one!” This was a response I got some years back from a like-minded friend. We had the same theology, but very different orientations toward the need to learn and study culture. This division among reformed believers persists, and it’s an area where greater clarity is needed in order to serve the Church in her mission.

On a basic level, one could ask a married man if there is value in studying his wife and her unique personality. The response should be in the affirmative! Yes, knowing your wife’s unique personality is an important way to love, cherish, and care for her. Well, one way to think about culture is that it is group personality. Knowing and understanding it equips you to better love your neighbor.

But knowing culture also allows you to powerfully illustrate the truth of God’ word. Notice the orientation here, because it’s vitally important that we don’t get it backward. The truth is coming from and grounded in God’s word, not the culture. The culture is used to powerfully illustrate that truth. This is the concept behind Don Richardson’s writing about redemptive analogies, of which Peace Child is one famous example. Missionary biographies are replete with stories of breakthrough coming when a missionary was able to explain or illustrate biblical truth in a category or legend the culture already had. If you have read Bruchko, you will remember how the legend of the return of the creator God’s “banana stalk” would lead to the opportunity to be reconciled to him again – the pieces clicked when the villagers saw the layered “pages” of the banana stalk as representing the pages of the missionary’s Bible. This is also what Paul is doing in Acts 17, illustrating the truth of God’s word through the Greek poets, such as Epimenides of Crete. We ground our message in the Word of God; we illustrate that message by knowing the culture deeply.

We still have so much to learn about our Central Asian people group’s culture, but there are a few illustrations that we have found that can help when a local objects to a certain biblical idea.

If someone objects to the idea that one can bear another’s sin, I like to bring up the old tribal concept of a woman for blood. If a man kills a man from another tribe, then honor requires the victim’s tribe to kill that man or someone else from his tribe, most likely starting a blood-feud. In order to avoid this, however, the murderer’s tribe can give a bride to the victim’s tribe. When a woman from the guilty tribe marries into the victim’s tribe, the murderer is counted righteous. She has paid the price for his sin. Her life is given in exchange for his.

Or again, if a local insists that Islam refuses the concept of substitutionary atonement, I bring up the accepted Islamic tradition that someone too old or sick to go on Hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca can pay for someone to go in their stead. Muslims believe that as that representative is rounding the Ka’aba seven times, the elderly person’s sin back home is being forgiven. One man is paying the sin debt another man could not pay, despite Islam’s insistence that it’s impossible for Jesus to do this on our behalf.

Sometimes locals insist that the idea of a plurality of elders/pastors would never work in their culture. They insist that only strong-man style leadership is effective in the Middle East/Central Asia. But I can bring up the old tradition of tribal elders, whom the chief was obligated to consult for important decisions. My friend may only know about domineering leaders and dictators, but if he talks to his grandpa, he will learn that yes, a plurality of leaders has deep roots in his culture.

One more example. My local friends will sometimes brag about how Islam permits them to have multiple wives. But I can bring up their proverb, that a man with two wives has a liver full of holes. I can emphasize that the wisdom of their ancestors actually agrees with the wisdom of the Bible, against the polygamy of Islam. So who are you with? The Bible and your people? Or Islam and the culture of your conquerors?

These examples show how biblical concepts (substitutionary atonement, plurality of elders, monogamy) can be taught from the word, but illustrated with the culture. It’s not that the culture ever provides perfect categories for these concepts. But the very fact that it provides categories at all means the argument that these ideas are merely foreign or illogical (and therefore to be rejected) can be defeated. These preexisting categories become beachheads from which biblical teaching and content can continue to push more and more into the culture and worldview of our friends. Sometimes a category doesn’t exist and it has to built from zero. But often there is a category there – a legend, a proverb, a tradition – we just need to keep on digging. God’s common grace has left even the most fallen of cultures loaded with hidden bridges to the truth.

In sum, learning the culture never has to be seen as a threat to biblical fidelity, as long as we are grounding our message in the correct place – the Word of God – and using the culture as means of illustration and appeal.

To support our family as we head back to the field, click here.

For my list of recommended books and travel gear, click here.

Photo by Jason Jarrach on Unsplash

Don’t throw stones into the spring from which you drink.

local oral tradition

Amazing that different cultures even need proverbs like these. Such is the self-destructiveness of sin and folly.

Photo by Kouji Tsuru on Unsplash

There I stood at the counter, like a tree kangaroo in the headlights. The fast food worker in his visor and apron was clearly a little perturbed.

“Wait, I get to choose what bread I want? Um… what kinds do you have?” I did my best to make sense of the various options I was given, nodding as if I had actually heard of them before. “Um… Italian!”

“Cheese,” the worker then mumbled.

“Oh no,” I thought to myself, I have to choose the cheese too?” So I asked again, “Uh, sorry, what kinds of cheese are there?”

The worker sighed and rattled off, “American, cheddar, provolone, pepper jack.”

“…Cheddar, I guess.”

“Veggies?”

What was with this place? Didn’t they know that they, as the ones who work at the restaurant, are the ones responsible for making these decisions, expertly putting together delicious flavor combinations so that I could just pick the one that looks the most delicious from its picture? Why were they asking me to do their job for them?

“Sauces? Toasted?” This guy was relentless! And I was getting nervous. I noticed one of my new classmates nearby was clearly enjoying this exchange. Time to bring in an interpreter.

I whispered, “Laura! Is this normal? Help!” Laura composed herself, graciously intervened, and helped me navigate the rest of the unnecessarily-complicated sandwich process.

I, a missionary kid from Melanesia, had now ordered my first Subway sandwich ever. It was a decent sandwich, but I have to admit I was a bit rattled. It took me a while before I was ready to brave the Subway sandwich interrogation line again. Perhaps this even played into my working later for the competition, Jimmy Johns.

The most daunting place for a missionary kid is their passport country, the country which is supposed to be their home. This is because Missionary kids (MKs, or Third-Culture Kids – TCKs) thrive in the role of the obvious outsider. They have grown up in countries and cultures where it’s clear that they are foreigners, and thus shouldn’t be expected to know the unwritten rules. Most cultures give a certain grace to outsiders, and MKs find themselves at ease in this kind of relationship. They are glad to play the respectful learner and guest. Many cultures also give a certain honor to those outsiders who have surprisingly assimilated, and MKs also thrive in playing this role. It’s just plain fun to be a foreign kid who is able to speak the local language, cook local food, and play local games.

But when MKs come back to their parents’ country, they are often expected to be cultural insiders. The fact is they are not cultural insiders. While their parents have passed on some aspects of their home culture, there are big gaps. MKs in their home culture can sense that there are unwritten rules functioning, things they’re expected to pick up on, but they’re not picking up on them. And no one has spelled them out. They can feel like they are in one of those dreams where it’s exam day, but somehow you showed up for the test without studying, and then you realize you’re not even wearing any pants. MKs are very adaptable, and might play it off like none of this is happening internally, but these dynamics are often present, especially from junior high through the college years. They aren’t as much of an issue for younger MKs, who are mostly free to enjoy the strange adventures of the motherland as a kinfolk-filled curiosity.

Why is it so hard for MKs to seamlessly pick up on the culture of their passport country? It probably has to do with the nature of culture itself, which is fluid and regularly changing, and with the way in which culture is typically learned – more by osmosis than by direct teaching. Learning culture just takes time, years of it. When I would share in my college years in the US that I grew up overseas, I would often get an “Oh, that makes sense!” response. It took quite a few years before the responses shifted to, “Oh, really? Wouldn’t have guessed it.” Over time, you assimilate, you “catch” things you were missing or someone just spells it out for you. “I was supposed to be tipping my barbers this whole time? Oh, no!”

If you get to spend time with MKs who are back in their home country on furlough/stateside or for school, there are ways you can help. You can offer to be a safe interpreter. Not all MKs are the same, of course, but for many it would be very kind and appropriate if you offered to field any and all questions they might have about their home country. Ask if there are things they find confusing or strange, or even difficult. Try to be observant of MKs in situations where they might be feeling out of place or unsure of what to do or say. Offer to go with them if they’re attempting something for the first time. If they get embarrassed, try to engage, ignore, or laugh with them as seems most kind for that particular person and situation. Like an employee in a retail store who asks if you need any help finding things, you might get rejected at first, but if you invite communication, you just may find your MK friend coming back to you later with some good questions.

We MKs and TCKs are a complicated bunch, but just like anyone else, we need good friends who will take the time to talk and listen and process… and occasionally help us order sandwiches.

To support our family as we head back to the field, click here.

For my list of recommended books and travel gear, click here.

Photos are from Unsplash.com

Much can be learned about a culture by identifying its ideal person. This ideal person, or figure, embodies the core values of said culture. How this figure lives and what this figure stands for will represent the corporate identity of a certain culture. He is, in some way, the culture boiled down, the incarnation of what is deepest, most valued, and most real. The cowboy of the American West is just such a figure for traditional American culture. He embodies the self-sufficiency, the self-determinism, the radical optimism, and the values of liberty, justice, and equality that so permeate American society. If one wishes to understand American society, studying the cowboy would be an good place to begin. My Canadian pastor says that the Mountie plays a similar role in the culture of our northern neighbors, with its greater emphasis on orderly westward advance rather than gun-slinging.

If the cowboy is the representative figure for America, the Bedouin nomad is the representative figure for much of the Islamic Middle East and North Africa. The Bedouin nomad embodies the core values of Middle Eastern culture. Ed Hoskins, a scholar who has studied Islamic culture extensively, writes of the Muslim’s view of the Bedouin:

Bedouin men and women are admired, emulated, and lionized… [Bedouins are] bold, chivalrous, proud, sentimental, pious, and honorable. They are free – unbound by most restrictions and limited only by their own strength – as well as ceremonial, decent, dignified, and true to their promise. They are discrete, ascetic, generous, grateful, obedient to parents, loyal to friends and relatives, and honoring of the elderly. They are firm, stable, patient, and persevering. Nearly all Muslims strive to live up to these standards.

Want to better understand the soul of Middle East? Learning about the Bedouin would be a good place to start. And when it comes to any culture, it’s worth asking, “Who is the ideal figure for this people?”

Edward J. Hoskins, A Muslim’s Heart, p. 9

To support our family as we head back to the field, click here.

For my list of recommended books and travel gear, click here.

Photo by Fabien Bazanegue on Unsplash