Twelve years ago I was standing just outside a stationary store near the center of the bazaar. The owner engaged me in conversation, curious as to where I was from. He eventually asked me how old I was, and I responded accordingly, being a twenty-year-old at the time.

“You’re still a child!” the man exclaimed.

I smiled and gave a respectful nod – it was not the first time I had heard that one, and certainly not the last. At thirty two, I’m still getting it.

“But when will I be a man, sir?” I asked.

The man lifted his index finger in the same manner a local teacher would, squinted one eye at me and said, “Son, when you have a wife, a son, and a mustache… then you will be a man!”

I pondered this response and thanked the shop owner for his helpful advice. Interesting ingredients for basic manhood, not too shocking, but a bit different than manhood might be parsed in other cultures. Especially the mustache. This was a few years before they made a comeback in the global hipster movement.

In our Central Asian culture there is no initiation-into-manhood ceremony, unlike many of the tribes in Melanesia. Marriage practically serves as the most commonly accepted threshold. But many locals would probably agree with the shop owner’s traditional response. Like most Westerners, I can’t really tell you when my culture actually decides that a boy has become a man. Is it the driver’s license at sixteen? The right to vote and join the military at eighteen? Becoming of legal drinking age at twenty one? My year as a single overseas, for me, served as the clearest point of entering “manhood” with its responsibilities and shift of perspective. The head of my org even pronounced me a man after I had completed my year and joined him for a coffee back in the US. Not a bad way to do it, taking a gap year to share the gospel among an unreached Muslim people group. There have certainly been worse ways to be initiated.

I agree with many that a biblical anthropology is the need of the hour for the Western world – a solid understanding of what the bible says about men and women, their differences and their similarities. What is the core of biblical manhood according to the scriptures? And what is the core of biblical womanhood? These are not small questions. They are questions my wife and I wrestle with as we raise two sons and one daughter in between a Central Asian culture with very restrictive gender roles and a home country that has seemingly smoked something awful and sailed off the edge of the world when it comes to sex and gender.

In Central Asia, because of what we believe about the equal worth and dignity of men and women (Gen 1:27), we are considered feminists. In the US, because of what the Bible teaches about natural distinctions in the roles and wiring of men and women (1 Tim 2:12-13), many would consider us backward-thinking misogynists. We live in between, trying to challenge both and carve out a healthy biblical path.

This is a huge subject, so I want to merely make a few general points, in the hopes of returning to each in more detail in the future.

First, we need to acknowledge that the Bible really does speak to a certain universality of femininity and masculinity. There is a core there that does not change from age to age or culture to culture. If biblical manhood and womanhood are like two huge oak trees, we need to take note of the fixed roots and trunk.

Second, we need to be honest about what the Bible does not say regarding the practical expressions of masculinity and femininity. For example, there is no biblically prescribed initiation into manhood or womanhood, despite what certain books in the Christian bookstore might say. Like so many other areas, we have biblical principles and we must work to faithfully express them in our unique contexts and cultures. We also need to study the cultures the Bible was written in. Some of the commands and examples in the scriptures are rooted in the created natures of men and women (and are thus universal, like 1 Tim 2:12-13) and some were applications of these deeper realities meant only for a given context (like the head coverings in 1st Cor 11). Returning to our two oak trees, we need to look up and acknowledge that when the wind blows the branches do actually have quite a bit of sway. Solid, fixed roots and swaying branches can coexist as part of the same healthy tree. The roots and trunk are our principles, the branches the healthy expressions.

Third, we need the global church. This is because we are all so prone to confuse our principles with our own cultural expressions. Being a man in America means I don’t hold another man’s hand, whereas I might be expected to in Melanesia or Central Asia. Manliness is often communicated in the West as a rough, unkempt sort of look, whereas Central Asian manly men are into immaculate grooming, poetry, flowers, and drinking tea from small dainty glass cups. Be careful if you laugh though, they all know how to jerry-rig the electricity as well as shoot an AK-47. Yes, while also wearing skinny jeans. Melanesian manly men weep severely and publicly, while Western manly men tend to keep their grief more private. Why the differences? Are they all equally valid or unequally skewed? Too often the biblical manhood camp in the West (of which I’m a part) has confused biblical manhood with things that are just frontier manhood – things like camping, steel-toed boots, radical individualism, guns, and cigars. Those are sometimes fine expressions of manhood, but they are also merely one culture’s unique expression of biblical principles such as courage (1 Cor 16:13) and subduing the earth (Gen 1:28). Exposure to the global (and historical) church will help us as we seek to get clarity on the faithful range of expressions of biblical manhood and womanhood. Those who have the privilege of international travel or living nearby internationals will have a practical advantage in this effort. Those who don’t resonate as well with their culture’s preferred expressions may find surprising help there as well. And for anyone who reads, the global church is increasingly accessible!

When did I become a man? It probably had very little to do with a mustache. Rather, it must have been at some point when the Lord acknowledged the growing presence of core things like servant leadership, courage, costly obedience, faithful work, and gentle strength. Ultimately it was in relation to him, and not some cultural ceremony, where the true shift of identity must have taken place. For what is biblical manhood or womanhood except coming to increasingly reflect the image of God according to our unique male and female creation? In that sense I have crossed a threshold and become a man. And yet eternity bears on this also. Having become a man, turns out I will never actually stop becoming one. Eternity means there’s always room to grow more like the infinite glory that manhood and womanhood together reflect.

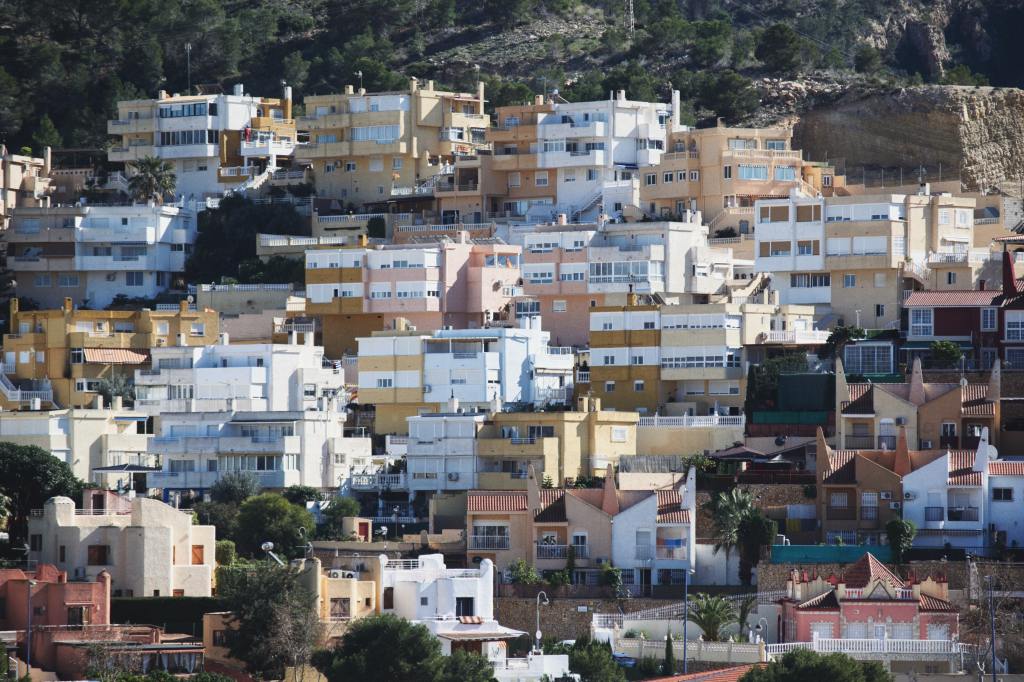

Photo by Josh Rocklage on Unsplash