My first friend in Central Asia, Hama*, was an eclectic fellow. He was a jaded wedding keyboardist who had lived for a number of years in the UK. This made him relatively progressive in relation to his culture. However, he still retained a deep appreciation for some of the most traditional places and experiences in the bazaar, things that most of his peers were distancing themselves from in their quest to be more modern.

For example, Hama was always ready to take me to eat a traditional dish eaten in the middle of the night, called “Head and Foot,” which could in some ways be compared to the Scottish dish called haggis. The base of Head and Foot is spiced rice sewn up in a sheep’s stomach, boiled in a broth made from the sheep’s head and feet. Sides include tongue, brain, and marrow. I usually just stuck with just the stomach rice and the broth. Paired with fresh flatbread this was a little greasy, but not bad. One intern who decided to eat all the sides as well, and record it for social media, ended up in the hospital. To be fair to the local cuisine, it was the middle of the night and it was his first time and he had also insisted on smoking a Cuban cigar immediately after eating brain and marrow. It may have been this peculiar combination of factors that did him in. As for the locals, the younger generation are starting to turn up their nose at Head and Foot, though the more traditional types still love the stuff. One incident several years ago involved a group of disappointed customers shooting up a Head and Foot restaurant with AK-47s because by 2 am they had already sold out.

But Hama was raised in one of the oldest bazaar neighborhoods, and something about things like Head and Foot spoke to his sense of where he came from. Perhaps it was his years living in Europe that awakened this appreciation in him. Or, like me, he was simply an old soul who found himself strangely drawn to the old ways, as if searching there for a hidden joy and wisdom that is almost out of our reach.

After finishing Head and Foot, the proper order of experience was to have a cup or two of sugary black chai, then to head to the traditional bathhouse. As far as I can tell, these bathhouses have their roots in old Roman culture, which eventually led to them spreading across North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia, remaining well-used there even when bathing became unpopular in medieval Europe. The most well-known of these distant Roman descendants would be the Turkish bath, but similar types of bathhouses are spread all over the region. In previous generations they served a very important public function: providing an accessible place where locals could get unlimited hot water and get deeply clean.

It’s only been in the last twenty years or so that hot running water at home became common for most of my peers in our corner of Central Asia. Before that, locals relied on visiting the gender-segregated bathhouses to bathe once or a couple times a week. Those as young as their mid-thirties grew up singing a song in grade school that went, “Today is Thursday; How wonderful; We go to the bathhouse!; Grab the soap; It’s on the window sill like someone sticking out his tongue at us.”

Even now the bathhouse provides a more reliable source of piping hot water than most homes, given the unreliability of government electricity. After Hama introduced me to the bathhouse in the fall of 2007, I found myself a frequent customer there that winter, the coldest the city had seen in forty years. With next to no electricity, frozen pipes, and ice-cold cement walls at home, the bathhouse was one of the only places in the city I could actually get warm – and take as long a shower as I liked. The mostly older locals eyed this skinny nineteen-year-old American peculiarly, but eventually got used to me, nodding in understanding at our mutual appreciation for endless hot water in the dead of winter.

The bathhouses of our area are typically made up of three rooms. First, you enter the reception area where the proprietor’s desk is, in a room with cement or plaster bench seating lining the walls. On top of this bench would be carpeting, and up on the wall lockers and hooks. Lots of natural light streams into this first room from upper windows. This room is a pleasant temperature and is designed for rest, drinking chai, and changing. To enter the second room, you need to be changed into your towel and to be wearing the provided toilet shoes. This second tiled room is warmer and contains some showers and an open floor area where an employee gives somewhat violent back massages for a small fee. The third room is the hottest. This room is heated by fire constantly burning underneath the floor, the hottest point being a raised octagonal platform in the center. Lining the walls are small sink areas built into the floor, each with a tap for hot and cold, a metal bowl for pouring the water over your head and body, and a small cement stool to sit on.

Those in the third room can sit at one of the sink areas to wash, stretch out on a part of the hot tile floor, or pace or exercise to work up a healthy sweat. The violent massage man will also aggressively scrub your back here, again for a small fee. Traditionally, most would be completely naked in this room, but undergarment-wearing patrons are now also very common. Most bathhouses also include some private shower rooms in addition to the open bigger room.

In addition to the blessedly hot rooms and water in the dead of winter, I always enjoyed the bathhouse for the reset of sorts I felt physically from the inundation of hot steam and water, contrasted when needed with bowls of cold. I also have fond memories of sitting with Hama in the rest room afterward, contentedly sipping chai and having good conversation. As other workers in Central Asia have found, the traditional bathhouse can be a place very conducive to friendship and spiritual conversation.

The bathhouse also gave me a picture that will forever be etched into my mind’s eye. I’ve never seen anyone scrub as long or as intensely as those older Central Asian men in the third room. At times it seemed as if they were trying to rub their skin off completely – as if they were even trying to get deep down and scrub their soul. Methodically, intensely, even desperately, they would scrub and rinse and scrub and rinse, using copious amounts of the old olive oil soap bars, over and over and over again. As I came to learn more about the nature of Islam, the image of these old men, ceaselessly scrubbing and yet never satisfied, came to serve as a metaphor for the desperation of those trapped in a works righteousness system. Lacking a way to wash the soul, Islam and other man-made religions rely on external cleansing. And yet the consciences of adherents have moments – or places – where the superficiality of this external “purity” takes over, and like Eustace the dragon, they claw at themselves, physically or emotionally, trying in futility to get another layer of scales off.

Those old men would likely have witnessed war, genocide, honor killings, wife-beatings, sexual and physical abuse, betrayal, slander, greed, and hypocrisy. They may have been victims, or they may have taken part in many of these acts of darkness, leading to an ever-lingering odor of guilt and shame. No wonder they scrubbed the way they did, almost trance-like, trying, consciously or unconsciously, to maybe this time find some way to clean the heart. All in vain. No bathhouse can ever bring the cleansing the mosque has also failed to provide.

There’s only one who is pure enough to clean the soul. He starts from the inside out, sovereignly reaching into our souls with his purity and miraculously making the unclean clean. We also use water, yes, even an immersion in it, but not as a means to become clean, but as a sign that he has already made us so. There is only one source of true cleansing for these old Central Asian men, for all of us. They must hear of Christ.

It is an amazing thing to step out of the dark Central Asian winter into the warmth and endless hot water of the traditional bathhouse. It is even more amazing to step out of the dark freezing hell of this present age and into the warmth, cleansing, and salvation provided by faith in Christ. There we will also find the water endless – even eternal.

*names changed for security

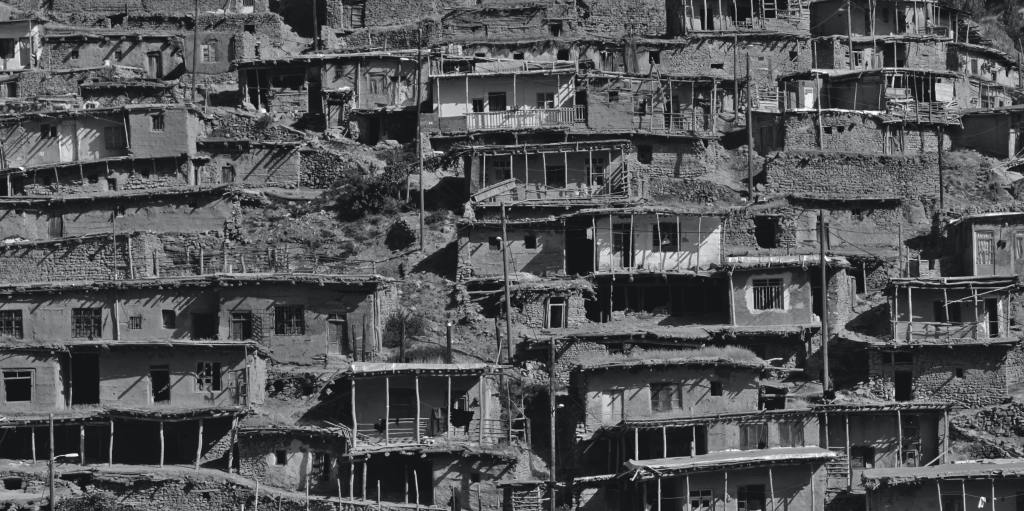

Photo by engin akyurt on Unsplash